We are asked to forgive our enemies, as core business of Christian life. How do we best forgive, in a culture of non forgiveness? Who and what should we forgive?

We are enjoined by our Saviour to forgive, not seven times, but seventy times seven. In other words, never stop forgiving.

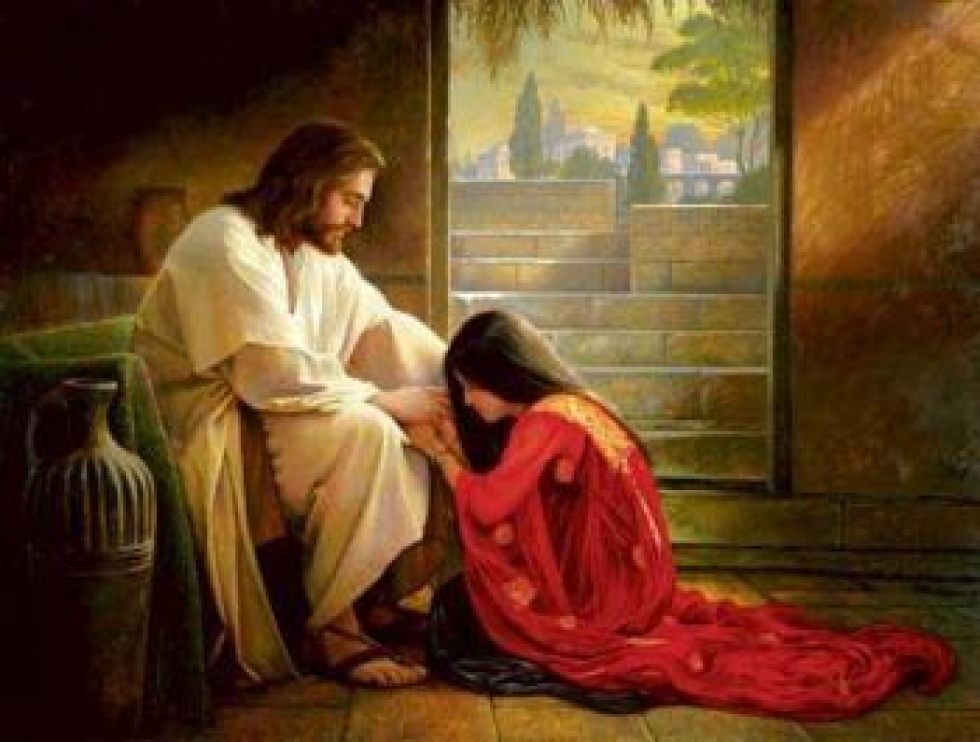

I would have to say that forgiveness is easier for some than others. I have an inclination to forgive. I can forgive individuals who do bad things in the abstract. This is, perhaps, an easy thing to do for great sinners like me. That same Saviour said, of St Mary Magdalene (my favourite saint, along with St Jude, St Paul – obviously – St Therese Martin, and St Joseph), that she loved much, and was therefore forgiven much. What a wonderful line, and a reassuring one. If only we could just love, like St Mary. Then we would be forgiven!

We are all fallen, we do bad things, routinely, and we all pray that we will not be defined and judged according to our worst deeds, but in recognition of our best selves. On the other hand, divine justice is there lurking just on the far side of mercy, and we want, as a default position, justice for “them wrongdoers” and mercy for ourselves. And it IS difficult, very difficult, to forgive those who have wronged us, or our loved ones.

The example of Cardinal George Pell is instructive. As an acutely intelligent and well informed man, he knows intimately the backstory to his own vilification and of his hounding by the State and its various instrumentalities. He knows all the wicked sins of the Church – after all, he was the one who began the process in this country of addressing them. He must see the irony of it all. It cost him his freedom and his reputation. Like the almost fatally shot St John Paul II, the falsely accused Pell has forgiven his “enemy”. It was an act, not of strategic cleverness, but of incomparable Christian forgiveness and charity.

Will Pell’s angry supporters – and I am one – be similarly forgiving of the Cardinal’s enemies, who include not only is accuser but many others? I fear I won’t.

Career progression, and the denial thereof, can be a severe test of forgiveness. As one who has been sacked from a job, with severe financial and emotional consequences, which only one who has experienced unemployment will truly know, I realise that the tests of one’s capacity and inclination to forgive can be sorely tested. One can be lured into vengefulness and endless self-justification, and an inclination to continually have a go at those who did you in. Including publicly. It isn’t pretty. Eventually you just get tired of the anger involved, and end up yearning to move on. Figuring out that there are more important things than “career” and the recognition that goes with it, helps, but this can take time.

We are all on a long journey towards mastering the art of forgiveness. It is a journey worth travelling. As many a thoughtful theologian has argued, it is the key to unlocking true happiness. If only more would take note.

Whatever the difficulties with forgiving those who harm us personally, whether intentionally or not, they are multiplied massively when considering forgiving the sins of “groups”. The twenty-first century world has taken on group grievances and their correction as its modus operandi. Identity politics rule everything. Captain Cook still has to pay (reputationally) for the then colonialist policies of the British Government. The Aboriginal activists continue to focus on claims for group justice rather than focusing on the individual welfare of their worst suffering people. New Zealand Maori leaders find endless solace in humiliating whitey at every turn. Feminists will never, ever forgive the Catholic Church – or men – for God’s decision to make women child bearers and rearers. Black American activists want reparations for slavery. Climate activists want something called “climate justice”, whatever that might mean. Sex abuse victims groups, the “Survivors” (with a capital S), are decidedly prone to no forgiveness, but rather, to the endless punishment of non-perpetrators who “could have done more”. Homosexuals want – well, I am not sure what they, as a defined group, want.

No student of American politics or viewer of US cable current affairs TV could ever be forgiven (no pun intended) for thinking that forgiveness is possible any time soon.

Hence the late Frank Devine’s marvellous line during one of the many controversies over Aboriginal injustice – I think it was during the apology controversy that so dogged John Howard’s premiership – that they “should simply just forgive us”. Only a devout Christian, perhaps, could say that. Yes, the Brits ruined your culture and took your “country”, but it ain’t really our (twenty first century Australians’) fault, and, can’t you just move on? Address the real problems with good policy, not driven by turbocharged acrimony.

And since there are now whole industries devoting to the non-forgiveness of enemies, whether British colonialists, or men, or whites, or the Catholic Church, or priests, or heteronormative types, there are massive institutional barriers to forgiveness. So many resources are now invested in non-forgiveness, with often lucrative monetary rewards attached, or power at stake. The default position among corporates AND governments is now one of compulsory attention to grievances.

Two of the great causes of facilitating, indeed embedding, non-forgiveness in contemporary culture are social media and the 24 hour news cycle, cable TV driven media world. Between these two “advances” in our infotainment driven world, they have weaponised our inherent urges to air grievances, bear grudges and project hatred on the back of myriad slights against our group identities. The slide into ideologically driven positions on every issue has only worsened since these developments have occurred. With our smart devices at the ready, non-forgiveness is only ever a click away. And social media platforms are addictive as a means of revealing our worst selves. I am as much a victim of this addiction as anyone else.

Social media has, for example, enabled “cancel culture”, the non-platforming of enemies, the perpetuation of ideological hatreds, and the cult of unfriending. This might all have happened without social media. But social media makes it brutal and final, in many cases where reputations, careers and livelihoods have been lost. All for a higher, ideological purpose.

When so much of the world is angry, what hope is there for that most meek of the many meek Christian virtues – forgiveness?

Yet we who live in this non-forgiving age and are often ourselves culture warriors are ourselves dogged by the counter-cultural Christian message. Forgive us our trespasses, “as we forgive those who trespass against us”. What is the best way forward, in public life especially?

Forgiving the sins of public figures caught out doing wrong – there, for the grace of God, go I – can be managed, as can my own capacity to look not unkindly on those who have sinned in their own lives, coming as I am from a self-recognised, fallen position. Acknowledging that forgiving those who have wronged us personally is a tad more difficult, but that, too, can be worked on.

The really hard part is forgiving institutions for institutional wrongdoing.

Our own capacity for not forgiving institutions can be idiosyncratic. I have trouble ever forgiving the Liberal Party for what it did to Tony Abbott. In a way I can forgive Malcolm Turnbull personally. He is like that. He routinely stabs those in the back who get in his way. He is on a mission, and nothing is going to stop him. The bigger sin, for me, lay with those in the Liberal Party who fell for it, and who destroyed possibly the only really decent man we have seen in Australian politics for a generation. An institutional sin – that I cannot forgive. So I will never vote Liberal again. Ever. Whatever the circumstances.

I have trouble, too, forgiving the Nationals for their advocacy, against all earlier expectations of them, for advocating same sex marriage and radical abortion laws. It is especially hard when one has previously devoted time and energy to these organisations.

We will all have our own examples of non-forgiveness of institutions.

Yes, I am a notorious non-forgiver of institutional failings, whether in political parties which abandon their decency and their principles, in institutions of justice who abandon the innocent, in corporatised sporting bodies which have turn sport into a business and ruined it for many, in my own Catholic Church for its supine acceptance of State power in relation to the COVID scare, in all levels of Government, and in corporations now at the mercy of their woke Human Resources departments who live only for their own corporate images.

Should we, therefore, expect others to forgive the institutions which we believe in, indeed belong to, for their wrongdoings?

Those of us involved in the defence of Cardinal Pell will also have felt, like everyone else, revulsion at the heinous cries and sins of the paedophile priest class. Yes, a small minority that was and perhaps still is involved, but nonetheless corporately “unforgivable”. Cardinal Pell ventured the counter-cultural comment in his interview with Andrew Bolt that he was trained to resist “gossip”, to treat sexual failings as a sin not a crime, and to forgive those who repented. Gerald Ridsdale? Where does forgiveness begin and end? The “Pell rot in hell” brigade still would appear to have some distance to travel.

We ashamed Catholics are probably even less forgiving of the paedophile priests than are the victims groups – if that is possible. For these men have succeeded, where everyone else, including Joseph Stalin, failed, in bringing our Church to its knees.

So, the barriers to forgiveness in our world are immense.

There are no easy answers to the injunction to forgive one’s enemies – seventy times seven times – in a non-forgiving world, where the very basis now of politics is to feel hatred and to seek compensation, indeed revenge, for the sins of past individuals and of their institutions.

We may look to the saints and the theologians to provide guidance, grace and spiritual nourishment. We can say, daily, “forgive us our trespasses as we forgive those who trespass against us”. We might even believe it, or wish to. But we sadly inhabit an unforgiving world which mocks meekness where there are ideological enemies to be fought, a world where our “factory settings”, to quote Bridget Phetasy, are designed to set us up for endless battle, with enemies to conquer, slights to be avenged, and power to be attained, with no prisoners to be taken.

Not much forgiveness, and not much love.