There are Two Leos the Great. One was a famous pope. The other was my father.

This time, as they say, it’s personal.

This coming Tuesday, 10 November, is the memorial of Leo the Great. St Leo (AD 400 to 461, pontificate 440-461) was a Pope of consequence, a Doctor of the Church, a Roman aristocrat, a lawyer, a liturgist exemplar, a theologian of “yuge” import, a diplomat of such sublime skills that he convinced a surging Attila the Hun to retreat from Rome. And simply go home. He set up the See of Rome as the authoritative seat of the one true Church, which lasted for many centuries, until some of his successors blotted their copybooks and caused Martin Luther to have his hissy fit. The rest, again as they say, is history.

Pope Leo’s remains rest very close to those of that other famous pope, Peter, in the Basilica of the same name in Rome. Surely a mere “memorial” is insufficient recognition of Leo by the Church.

With Pope Gregory the Great, Leo is the only pope ever to be deemed a Doctor of the Church. 260 odd popes (and some of them have been odd), and only two doctors. There are two late twentieth century and early twenty-first century popes who, surely, await a similar accolade. There aren’t too many “greats” either. St John Paul II has his fans for such recognition, and I won’t argue with that.

A Doctor of the Church is a saint whose writings have “special authority”.

Leo qualifies, in spades. He was a patristic father of the Church, a rough contemporary of the great Augustine, who through his Council of Chalcedon affirmed and defined Christ’s divinity AND humanity in the face of some sadly influential recalcitrants (heretics) who just didn’t get it. His Letter 28 was simply called “the Tome”.

His eloquent spiritual writings survive to this day, and provide core readings for the priests who are forever faithful to saying their Daily Office. He matters. Still.

Attila the Hun was a presence in his day, clearly. (Whether he was remotely right wing is another matter; perhaps he was alt-right). He got to the outskirts of Rome, with malevolent intent, then was confronted in person by the Pope. Attila’s reasons for seeing sense are disputed. Pope Leo had serious muscle at his side, so the story goes. But he also had divinely inspired charisma and was, by all accounts, sublimely persuasive. He may have offered Attila rewards for retreating. He was, no doubt, a foreign policy realist. So it went.

November the tenth is also the birthday of another Leo the Great. My father.

Pope Leo died on 10 November. My father was born, in Cowra, New South Wales, on 10 November 1908. Leo’s parents, Catholic believers both, surely had something in mind when they so named their first born.

That family tradition has carried though, delightfully, to my own grandson, Peter Leo Collits.

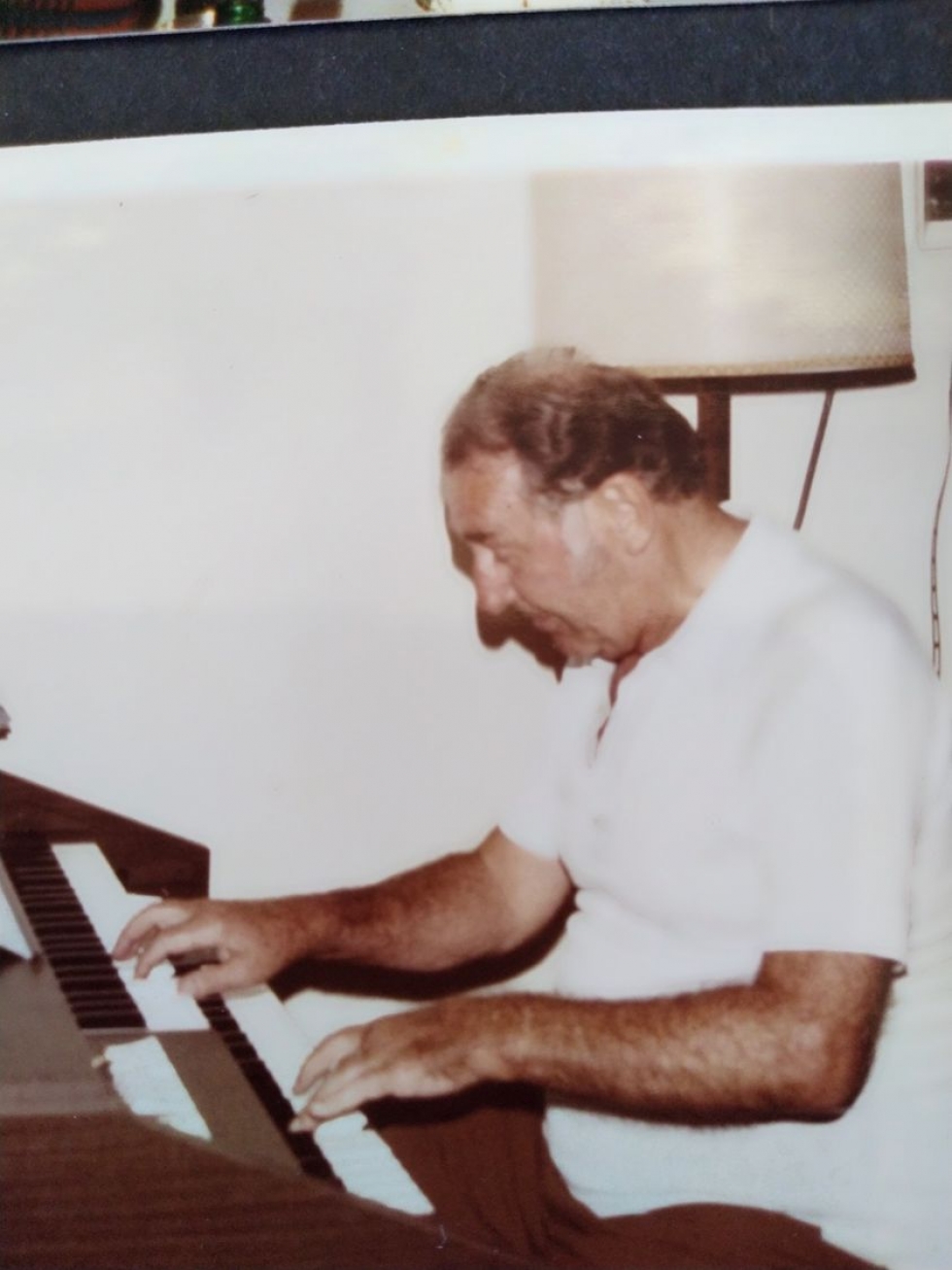

Like his Roman namesake, Leo Collits had his own charisma, in spades. He was a dedicated father, a faithful husband, an outstanding cricketer, a teacher of renown, a sublime pianist and composer, and a flirt of some consequence (so I am told). He was a personality. He also probably suffered from depression – he was moody – not then recognised for its sinister impact and probably experienced by many creative. He was cut down, after a lifetime of heavy smoking, by ten years of awful asthma that led to his early death at sixty-eight. That was 1977.

Like his papal namesake, Dad’s life was consequential in its way.

Dad moved around a lot in his childhood, as his father Harold was an employee of the Posts and Telegraphs. He got to know regional New South Wales, with stints in Moree and, eventually, Gosford. His love of music and his special skills emerged early. As a teen, he played the piano at the Regal Theatre in Gosford for the silent movies. He didn’t complete secondary school, but later trained as a primary teacher. They say that mathematics and music are closely connected.

He met my mother at The Entrance. When Mamie was delivered by her mother to her own first teaching gig at Dad’s school, he offered on the spot not only to mentor Mum but to marry her! And, after some years of Depression difficulties later, he did.

Dad was an extraordinarily gifted cricketer.

A leg spinner. He represented the Central Coast for years. As a callow youth, watching a seniors’ game at Graham Park (now Central Coast Stadium), he started bowling wronguns to senior players on the sidelines and was suddenly recruited to be part of the senior team. He never left. Unlike Shane Warne, he could bowl wronguns at will and land them on a dime. He once bowled to Bradman, with whom he shared a love of the piano. The Don was a musician of note, and has bequeathed to us a granddaughter, Greta, who is a classical music star.

Dad’s younger brother Jack was a star batsman in his day, only later in life to succumb to the demon alcohol. This crushed Dad. I knew Uncle Jack. He was a lovely, deeply flawed man. It ended badly.

Dad spent many an hour bowling to me in the back yard at Gosford, with a concoction of finger spin, wrist spin and googlies, and my own love of the great game and my own modest batting prowess is solely down to him.

Dad wrote the music to Gosford High school song. He also wrote the music to the school song for my own alma mater, St Edward’s College. Dad was a musical genius.

He could listen to a song on the radio, then go to the piano and play it. I have never seen anything like this in my life. He understood rhythm, and beat. He loved, and interpreted with rare perception, the great American songbook. He loved Bing, and Frank. He got the Beatles, without perhaps ever being a complete convert. He understood their musical genius. He entertained the family with his astonishing playing, when the mood took him, after Sunday lunch. For hours on end. From Beethoven to the Carpenters. This was rare musical genius, humbly contained and constrained in the life of a journeyman secondary school music teacher in suburban Gosford. They made a movie about my father, without intending it. It was called Mr Holland’s Opus.

Dad befriended our local priests and Christian Brothers as a matter of course, in days when Catholic culture was a real thing in communities like Gosford. He was a pioneer of Catholic education in Gosford.

He loved the Christian Brothers. What on earth would he make of the devastating revelations that have since come to light about that once loved order? There were creeps at St Edward’s in the 1950s. They prospered and continued their nefarious pursuits into the seventies. Dad wouldn’t have known, remotely, nor would he have understood. Paedophilia would have been simply incomprehensible to him then. As it would have been to all of his (perhaps naïve) contemporaries. He might have understood, instinctively, the account of the Christian Brothers and their very difficult lives rendered by that very talented Australian writer, Barry Oakley.

Dad, as Music Master, taught just about every student who went through Gosford High from 1948 to 1968. They all knew him, and remembered him with massive affection. They loved him. He instilled in them all a genuine love of music. I was taught music by two of his ex-students. Music is the love of my life, and I have Dad to thank for that.

He was a rugby league nut, and helped coach many successful Gosford High teams. He secured the great St George and Kangaroo representative, Ian Walsh, as a speaker at one of the sports presentation nights, and embarrassed me as a nine year old by insisting I come up to the stage to get Ian’s autograph. Dad also gifted me my lifelong devotion, seldom rewarded (alas), to Wests Magpies, a club cruelly cut down and eliminated in the 1990s by one Rupert Murdoch. Dad knew some of the 1940s Maggies personally.

Dad also taught me politics, and a lifelong enduring affection for the working class.

He was a Labor man, when the ALP was a very, very different beast to what it has become today. He reflexively hated the Liberal Party when the contest of politics of one of relatively straightforward class politics. He harboured embedded opposition to crony capitalists, a position that I have never come to question. I have no idea what this Catholic man would make of today’s depressing wokedom and the Labor Party’s utter sell-out to its core, socially conservative roots. His former political love is now the party of abortion, of euthanasia, of mainstreamed homosexuality. It is a different world now, utterly diminished. I believe that Dad would be shaking his head now.

Dad had a tough gig during his Gosford years. He inherited his late father’s home when Harold died, but with the express condition to care for his ageing and quite difficult mother. That mission lasted some twenty years, and caused my mother considerable grief at times. Being caught between two women that you love, but who don’t get on, is not a comfortable place to be.

Dad was near fifty when I was born.

I only knew him, then, as an ageing and sickly man, debilitated, and he died when I was twenty. Knowing and loving one’s children as adults is something I have come to know to be one of God’s special blessings. It was not to be with my own father. My mother became carer for a tough decade, with hospitalisations interspersed with moments of relief and increasingly rare joy. It never remotely deterred her from continuing to love the man she first knew as a colleague, then suitor, then husband, at The Entrance during those dark days of 1930s depression.

But he was always Leo the Great to me. An utterly compelling presence. He still is. I am convinced that there are two Saints Leo, now in Heaven. I love him still. Come 10 November this year, just like every year, I will raise a glass, with affection and now, sadly, only long distant memory.